291x

Filetype PDF

File size 0.13 MB

Source: www.cambridge.org

File: Cbt For Health Anxiety Pdf 109373 | Div Class Title Cognitive Behavioural Therapy For Health Anxiety In A Genitourinary Medicine Clinic Randomised Controlled Trial Div

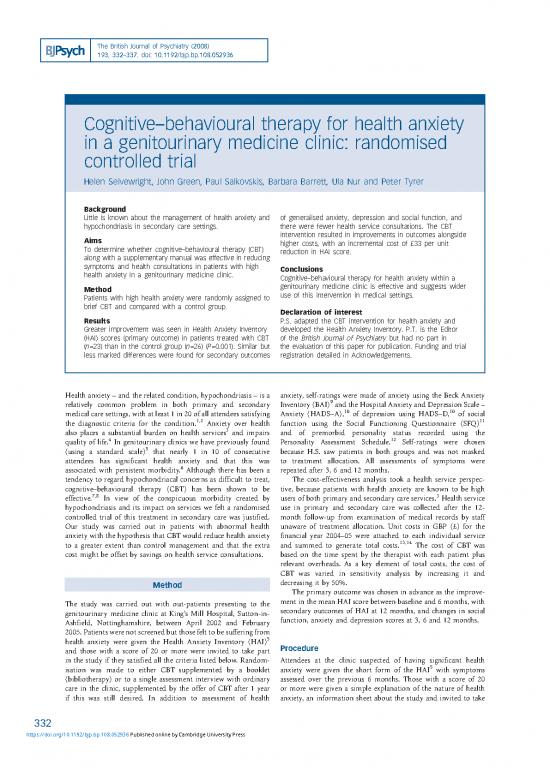

the british journal of psychiatry 2008 193 332 337 doi 10 1192 bjp bp 108 052936 cognitive behavioural therapy for health anxiety in a genitourinary medicine clinic randomised controlled trial ...

![icon picture PDF icon picture PDF]() Filetype PDF | Posted on 27 Sep 2022 | 3 years ago

Filetype PDF | Posted on 27 Sep 2022 | 3 years ago